An important exhibition has opened at the Government Museum in India since April 18, exactly on the International Day for Monuments and Sites, it will run until June 30, in Chandigarh, the idealized city designed and created by Le Corbusier. It is a photography exhibition, and the author is none other than the French ambassador to Delhi Emmanuel Lenain. What we didn’t know was that it was not the first attempt by Emmanuel Lenain. When he was based in China, Beijing and Shanghai, this genuine amateur of photography has documented with his Leica M6 the daily life and unusual places during his travels and visits, and he would develops himself and print his negatives in the darkroom of his residence. Before leaving China, he assembled his photos of China and published a book: “China, the Great Works”. This series was exhibited and screened at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris and entered its collection in 2016. After returning to the Quai d’Orsay and having served as diplomatic adviser to the Prime Minister, Emmanuel Lenain was appointed in 2019 as ambassador to Delhi. He wasted no time in sizing up this vast country so full of diversity and colors with his camera, always in monochromatic Black and White. There is no coincidence in the world of photography, the same year, in 2019, the most important Indian photographer Raghu Rai (member of Magnum) received the Photography Prize from the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris. The result of the encounter of the two photographers is a crossing of vision and a joint exhibition took place in 2022, accompanied by a book entitled “In India, to Paris”, where each one reveals and shares his singular vision and his own humanist sensitivity towards an “other” culture. .

India happens to be the country where the legendary Le Corbusier carried out his life’s work in Chandigarh, so it is only natural that Emmanuel would be attracted to the beauty and the spirit of the monuments designed by the visionary architect Charles Edouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, notably in Chandigarh, and in Ahmedabad, works that are still very much “alive and kicking”, as the title of Lenain’s exhibition “tender concrete” suggests. Because the key characteristics of Le Corbusier’s architectural works are based on the use of reinforced concrete. If Emmanuel Lenain has seen and felt the tenderness of concrete, perhaps he meant to express the plasticity of concrete, so remarkable Le Corbusier’s intensive use of sunscreens, double-skin roofs, the care given to orientation and openings to facilitate ventilation and aeration, in order to adapt to the local climate, hence the pilings, the long ramps, and the garden terraces. This tenderness can be found expressed through Emmanuel’s own observations, his shot angles, and the patient search for the “good” light, and his own reflections on the full and the empty, to manage to compose in the end, an abstract art painting à la Mondrian, all in monochromatic Black and White, while inserting his quest for diagonals and ellipses to vary and upset the monotony of straight, vertical or horizontal lines. The dizzying curves when ceilings and stairs merge in three-dimensional apparitions “deja-vu” in Escher’s drawings. And as on penetrated through the doors left ajar, the interiors feel like the imaginary spaces and labyrinths of sophisticated video games…

We are hooked and wanting for more…

According to the French Embassy in India: “The exhibition showcases Lenain’s personal and subjective approach to photography, capturing the beauty of concrete architecture. “I am not among those left aghast by Brutalism. Quite the contrary: concrete, when handled by the greatest architects, has always seemed tender to me. It allows for sensual and dizzying curves, the alternation of empty and full, a plunge into solitude and reverie. Concrete allows for a constant, almost musical tension: rectangle contrasts with curve, sharp edges with softened poles, static with fluid, rest with movement. Here and there, buildings of strict verticality and horizontality contrast with the freedom of a curved ramp. And, as is often the case, a certain harmony emerges from opposites,” said Lenain.

Text Jean Loh

Photography © Emmanuel Lenain

Tender Concrete

EL-Tender Concrete 01 Government Museum and art gallery Chandigarh October 2020

EL-Tender Concrete 02 Mill Owners Association Ahmedabad February 2021

EL-Tender Concrete 03 Government Museum and art gallery Chandigarh May 2022

EL-Tender Concrete 04 Lilavali Lalbhal Library Ahmedabad February 2022

EL-Tender Concrete 05 Tower of Shadows Chandigarh May 2022

EL-Tender Concrete 08 Secretariat Building Chandigarh October 2020

EL-Tender Concrete 09 Mill Owners Association Ahmedabad February 2021

EL-Tender Concrete 10 Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad February 2021

EL-Tender Concrete 11 Government Museum and art gallery Chandigarh May 2022

EL-Tender Concrete 12 Panjab University Chandigarh May 2022

EL-Tender Concrete 14 Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad February 2021

EL-Tender Concrete 15 Gandhi Bhavan Chandigarh May 2022

Emmanuel Lenain ou la tendresse du béton

Une importante exposition est ouverte au Musée du Gouvernement en Inde depuis le 18 avril, Journée Internationale des Monuments et des Sites, elle durera jusqu’au 30 juin, à Chandigarh, la ville idéale conçue et créée par le Corbusier. C’est une exposition de photographie, et l’auteur n’est autre que l’ambassadeur de France à Dehli Emmanuel Lenain. Ce que l’on ne savait pas, c’est qu’Emmanuel Lenain n’en était pas à son coup d’essai. En poste en Chine, à Pékin et à Shanghai, ce passionné de la photographie, documente la vie quotidienne et les lieux insolites au cours de ses voyages et déplacements, avec son Leica M6, et développe ses négatifs dans la chambre noire de sa résidence. Avant de quitter la Chine, il a rassemblé ses photos de Chine pour publier le livre « Chine, les Grands Travaux ». Cette série a été exposée et projetée à la Maison Européenne de la Photographie et entrée dans sa collection en 2016. Après un retour au Quai d’Orsay et avoir servi comme conseiller diplomatique du premier ministre, Emmanuel Lenain est nommé en 2019 en Inde, à Dehli. Il n’a pas perdu son temps pour appréhender ce vaste pays si plein de diversité et de couleurs avec son appareil photo mais toujours en monochrome en Noir et Blanc. Il n’y a pas de hasard dans le monde de la photographie, la même année, en 2019 le plus important photographe indien Raghu Rai (membre de Magnum) reçoit à Paris le Prix de la Photographie de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts. Il résulte de la rencontre des deux photographes un croisement de regards et une exposition conjointe en 2022 accompagnée d’un livre intitulé « In India, to Paris », où chacun dévoile et partage sa vision particulière et sa sensibilité humaniste envers une culture « autre ».

L’Inde c’est le pays où le légendaire Le Corbusier a réalisé l’œuvre de sa vie à Chandigarh c’est donc tout naturel qu’Emmanuel soit attiré par la beauté et l’esprit des monuments dessinés par l’architecte visionnaire Charles Edouard Jeanneret, dit Le Corbusier, notamment à Chandigarh, et à Ahmedabad, œuvres toujours vivantes, comme le laisse entendre le titre de son exposition : « la tendresse du béton ». Car les caractéristiques des œuvres architecturales de Le Corbusier sont fondées sur l’usage du béton armé. Si Emmanuel Lenain voit et ressent la tendresse du béton, c’est qu’il veut exprimer la plasticité du béton, remarquable dans le recours intensif au brise-soleil, aux toits à double peau, le soin apporté à l’orientation et aux ouvertures pour faciliter la ventilation et à l’aération, dans le but de s’adapter au climat local, d’où les pilotis, les longues rampes, et les terrasses-jardin. Cette tendresse Emmanuel Lenain le ressent et l’exprime à travers ses propres observations, ses angles de vue, la recherche patiente de la « bonne » lumière, ses réflexions sur le plein et le vide, pour arriver à composer un tableau d’art abstrait, à la Mondrian tout en monochrome Noir et Blanc, et en y glissant des recherches de diagonales et d’ellipses pour varier et chambouler la monotonie des lignes droites, verticales ou horizontales. Les courbes vertigineuses où les plafonds et les escaliers se confondent comme des apparitions à trois dimensions dans les dessins d’Escher. Les intérieurs ressemblent aux espaces et labyrinthes imaginaires des jeux vidéo sophistiqués… On aimerait s’en mettre plein les yeux, encore et encore.

Texte : JEAN LOH

Photos © Emmanuel Lenain

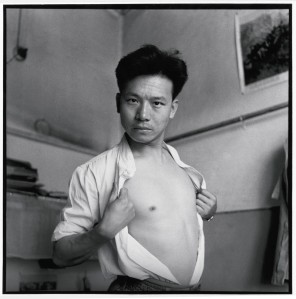

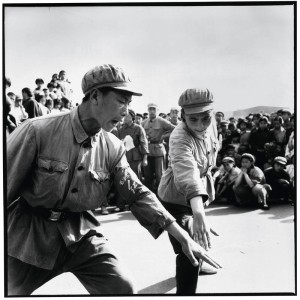

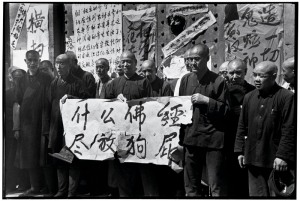

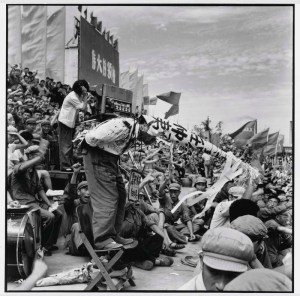

![aZheChen_02_[Bees 007-04]](https://sayshanti.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/azhechen_02_bees-007-04.jpg?w=300)

![aZheChen_03_[Bees 022-03]](https://sayshanti.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/azhechen_03_bees-022-03.jpg?w=300)

![aZheChen_06_[Bees 002-01]](https://sayshanti.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/azhechen_06_bees-002-01.jpg?w=300)

![aZheChen_10_[Bees 015-04]](https://sayshanti.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/azhechen_10_bees-015-04.jpg?w=300)

![aZheChen_24_[Bees 019-01]](https://sayshanti.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/azhechen_24_bees-019-01.jpg?w=300)

![ZheChen_13_[Bees 054-06]](https://sayshanti.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/zhechen_13_bees-054-06.jpg?w=300)

![ZheChen_14_[Bees 068-03]](https://sayshanti.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/zhechen_14_bees-068-03.jpg?w=300)

![ZheChen_20_[Bees 048-01]](https://sayshanti.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/zhechen_20_bees-048-01.jpg?w=300)